ICU Nurse to ICU Family (and Back)

February 13, 2019

Kathleen Turner, June 2016

In the first week of May, my mom and I went on a driving-and-hiking trip through Oregon and Northern California. Here she is on one of our frequent “where are we and how did we get here” map checks! Nine days later, my mom had a massive GI bleed and was admitted to the ICU in her community hospital in Washington, DC. I flew out and was there until the day she left the ICU. Thank you to the charge nurses and admin team for making that possible, and for your texts of support while I was gone. Here are some thoughts from my experience as an ICU family member.

It is a 100% powerless experience to be an ICU family member as opposed to staff. It had been my choice not to say I am an ICU nurse. Sometimes we share that kind of information in shift handoff as an asset – a family member who can decipher things for the others. Sometimes instead we convey a sense that the clinician family member may be judging and evaluating us. (Sometimes that’s true, but generally not, in my experience.) I didn’t want any of that to distract from my mom’s care. If my mom had been my patient, some things would have been done differently, but she wasn’t. I trusted that the nurses and doctors in that ICU were doing their best for my mom and cared about her (and my family’s) well-being. I didn’t have to be her nurse, just her daughter. How did they establish that kind of trust?

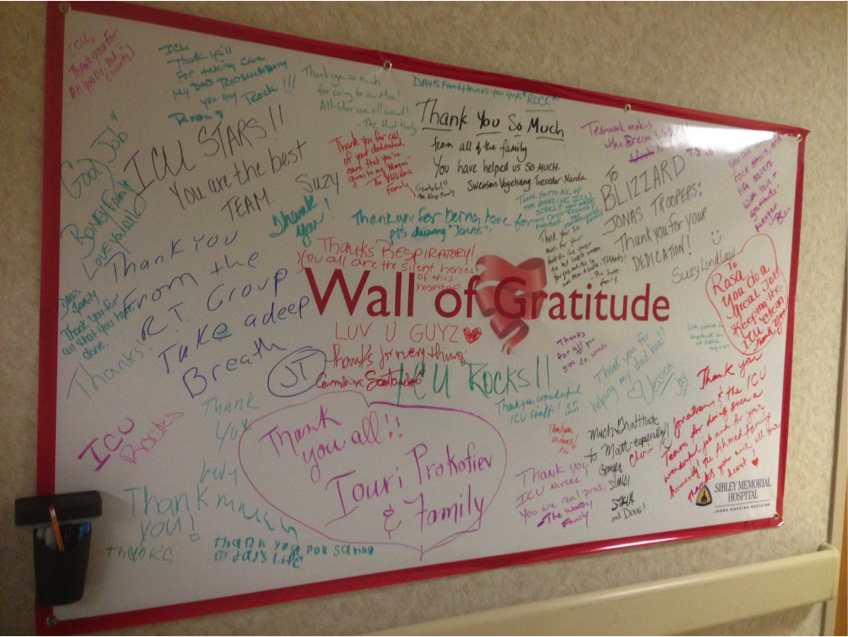

Welcome. When my sister and I got to the hospital on what was my mom’s second night, it was the first word I heard as security checked our IDs and made our badges. They told me where to go, and when I got to the ICU, there was a sign on the door saying “Please come in.” I was so shocked I took a picture with my phone. Coming in to the unit, there was a “Wall of Gratitude” sign, where patients and families had written to the ICU staff. Hard to put in words the relief I felt thinking of my mom in the hands of the kind of clinicians these families were describing. Across the hall were signs saying the unit’s last CLABSI was April 22, 2015 and they had been 89 days without a fall.

What else? It was after 10pm when we arrived, and my brother and dad were already at my mom’s bedside. After being welcomed by security, seeing the Please Come In, and passing the Wall of Gratitude, my sister and I were able to go right to her room. Seeing all of us together seemed to be strengthening and reassuring for my mom. She later reflected, “It made a HUGE difference when my whole family was all nearby – it was the first time I could begin to imagine that I was or would be whole again, too.” It was certainly therapeutic for my family, reminding us of all the tough times we’d already overcome together and planting the seed that we’d get through this one too. Usually we only had 2 or 3 people at a time in the room, but if the group got larger (I think the most was 6, when my niece and nephew visited) there was no pushback from the staff. Any time staff needed more space, we melted out of the patient care area and walked off our energy elsewhere.

Staff collaborated with my family. Example – when my mom needed to get up to the bedside commode, we learned where the commode should go and how to arrange the other furniture to clear a path. As soon as my mom needed to go and hit the call light, a family member would get the room ready. When the nurse or tech arrived, he or she could attend immediately to my mom and we would get out of the way. Another example involved helping keep an eye on my mom’s last IV. She is a tough stick and blew every IV she got. One regret of the ICU stay was not being present for the central line placement. I think it would have helped my mom feel less uncomfortable under the drape, but the option was not offered. I would gladly have gowned up and held her hand. In future, I will talk with ICU about offering that to my patients’ families. As it was, I was out in the waiting room, where I got to experience the freaky time deceleration that the PFAC has spoken about. I remember looking at my watch thinking we must be about 45 minutes into the line placement and wondering if maybe it was done – in fact, only 10 minutes had gone by.

In that unit, families are not asked to leave during shift change. From what I saw, there was a huddle at the very start of shift somewhere away from the nursing station. Nurse-to-nurse handoff seemed to happen in two stages – one at the desk that involved looking at things on the computer, and one at the bedside for assessment and drips. The nurses asked my mom and whatever family were present if we had any questions or information to share with them. The ICU attending came in and spoke with the us at the bedside every morning and PRN. These were not drawn-out discussions but more of a check in. “I hear X, Y, and Z are going on… how are you feeling… what are your thoughts about that… here’s the plan for the next few hours… your nurse is great.” I asked the charge nurse on one of the last days whether this family presence thing was normal or whether we’d just lucked out. She told me it is their unit culture. She said “I know we’re just a community hospital, and acuity here is not as high as where I come from, but I came from a level 1 trauma ICU and I had family at the bedside for handoff and rounds unless there was a reason not to. Can’t tell you how many times a family member filled in missing or incorrect information. We couldn’t have given as good care without them.” Again, this theme of families as partners.

I was nervous thinking about what my mom and my family might overhear in the ICU. For instance, the patient in the next room was delirious (just a guess – I did not sneak in and CAM him) and his BiPAP kept alarming. He was frequently crying out about stuff that often made no sense. He was also on contact isolation. It would be not unexpected that someone might speak sternly to him, nonverbally convey frustration with having to gown up yet again, or do something else inadvertently cringe-worthy. I’ve done it and I’m sure each of us has. I just didn’t want my mom or family to experience that. Instead, those nurses treated every interaction with that man as though it were their first. Offering comfort and support, explaining for the millionth time where he was and why he needed to wear the mask. I was proud of them. Just like with the Wall of Gratitude, a powerful message was sent and received – this is how we treat people here. Respect and dignity were reflected in each interaction – except one, more on that in a minute. When my mom was receiving personal care, her curtain was always drawn.

We could hear everything, just like families at UCSF and everywhere else. My mom complimented the ICU attending on how well he explained bronchoscopy to her next door neighbor! We learned about the nurses’ vacations, schoolwork, dinner plans, etc. There certainly was discord with the fear and sadness inside our ICU room, but these conversations also were a reminder that real life continued. My dad learned that our day nurse was from an area of Louisiana near where he went to grad school and they bonded talking about the food. What I did not hear were any disparaging comments about patient situations. My mom used her call light every hour or less, usually needing to get up to the bedside commode. There was not one word overheard about that. Not only great for respect/dignity, but for safety. Mom already felt bad enough troubling the nurses. If she’d had to overhear that it was imposing or that she should get a Foley or any of the usual things folks say in those situations, she might have tried getting out of bed herself and maybe fallen. Instead, those nurses came in with a smile, like they’d been hoping to get a chance to visit with my mom. Another thing that was notably absent – no one said anything about any GI bleed smells from patients. Maybe in the breakroom it was different, but out in the patient care zone there was nothing said. For my mom, who already felt dirty and gross, this was a blessing. This is a take home point for all of us. I worked in a pod over the weekend where there was quite a bit of blood in the air, and it was frequently commented upon. Let’s not.

Which brings me to the last story, the one negative interaction of the ICU stay. My dad and I arrived in the ICU on the last morning. A new GI doctor had rotated on and had just been in to see my mom. His bedside manner made her cry. As a daughter, I was so angry. When I asked my mom for the particulars, they sounded pretty familiar and I’m sure they will to you too. This doctor came in, did not introduce himself, stood at the foot of my mom’s bed and did not touch her at any point in time (even for exam), and contradicted the plan laid out by the ICU team. Mom’s primary nurse and the charge nurse were at the bedside as she was telling the story; Mom was concerned that she did not want to have her outpatient followup with this doctor, but she did not know his name. The charge nurse looked it up in Epic and gave it to us, and confirmed the name of the earlier GI doc she loved. As a family member, that was helpful because I’m confident my mom will go get the followup care she needs rather than potentially delay or have miscommunications because things got off to a bad start with the other doctor.

OK – really the end. My mom was only in the ICU for 4 days, and is home now. She is working through post-intensive care syndrome. I had not expected that or I would have put on my ICU nurse hat and prepped her and our family while I was still in DC. Note to self – you do not have to be on a vent for 3 weeks to go home with serious cognitive, emotional, and physical challenges. I scanned and emailed her the “What To Expect After the ICU” brochure we have in 9/13, which she found to be so helpful that she gave it to her primary care doc to share with any other post-ICU patients. Recommended! We’ve learned from Heidi and her crew that mobility is medicine and so my mom has already started outpatient PT. She has an ICU diary. She and the rest of my family benefit from all that I have learned from you over the years, and I hope there has been something in this overly-long piece that you can take and use.

Thanks for reading!